Northeast Wisconsin residents grapple with PFAS pollution

Ruth Kowalski can still remember the first time she read the unfamiliar acronym.

It was the fall of 2017, and Kowalski, 64, was standing in the kitchen of her Town of Peshtigo home holding a letter that had just come in the mail.

“It explained that there may be contamination in our underground water,” she said. “I was shocked. Very concerned. That’s when I started doing some research about PFAS.”

Per- and Polyflouroalkyl substances, more commonly known by the umbrella acronym “PFAS,” are a group of human-made chemicals used in a wide array of consumer and industrial products.

PFAS are characterized by their nearly indestructible molecular bonds, which make them an ideal component in everything from stain-resistant clothing to non-stick cookware. That molecular durability has also earned them the nickname “forever chemicals.”

But when ingested at high concentrations, PFAS can be detrimental to human health. The chemicals have been linked to a host of medical conditions.. And unbeknown to Ruth Kowalski and her husband John, PFAS had been accumulating on their property for years.

The source was just a mile down the road, in neighboring Marinette, where Tyco Fire Products operates a 380-acre fire training center. The company, which is now owned by multinational corporation Johnson Controls, manufactures foams that are designed to extinguish extreme types of fires, especially those containing oil and gas.

According to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Tyco conducted training exercises with the PFAS foam for more than five decades in Marinette. The DNR believes significant levels of PFAS from those foams made their way off of Tyco’s property through ground and surface water – and onto the properties of homeowners like the Kowalskis.

PFAS HITS HOME

Ruth and John Kowalski are both lifelong residents of Northeast Wisconsin. In 1981, the couple moved into John’s childhood home on County Road B in Peshtigo.

The property has a sweeping backyard with a line of trees that provide privacy from the road. It’s the kind of spacious and quiet setting that the Kowalskis wanted to raise their two daughters, who are now 39 and 40.

“It explained that there may be contamination in our underground water. I was shocked.”

It’s exactly the last place they expected to be at risk for chemical contamination. But once they heard about the PFAS pollution, the couple said they needed to know if they had been affected.

“We lived here long enough,” said Ruth Kowalski. “I wanted to have my blood tested.”

The Kowalskis opted to have a blood serum test to determine the amount of PFAS in their bodies. Results showed they both had elevated levels – Ruth had 55 parts per trillion, John had 110. But their doctor told them it’s unclear what that will mean for their health in the long term.

A sample of the surface water in the creek next to their home, where their daughters would often play, showed PFAS levels at 1200 parts per trillion. That’s more than 17 times the federal health advisory level.

The couple has now started doing their dishes with bottled water, which Johnson Controls provides for about 100 homes within the contamination zone. They no longer let their grandchildren bathe in their home when they come to visit.

“I’m appalled. Just appalled,” said Ruth, choking back tears. “For myself, not so much. But for children? How dare they?”

YEARS WITHOUT KNOWING ABOUT PROBLEM

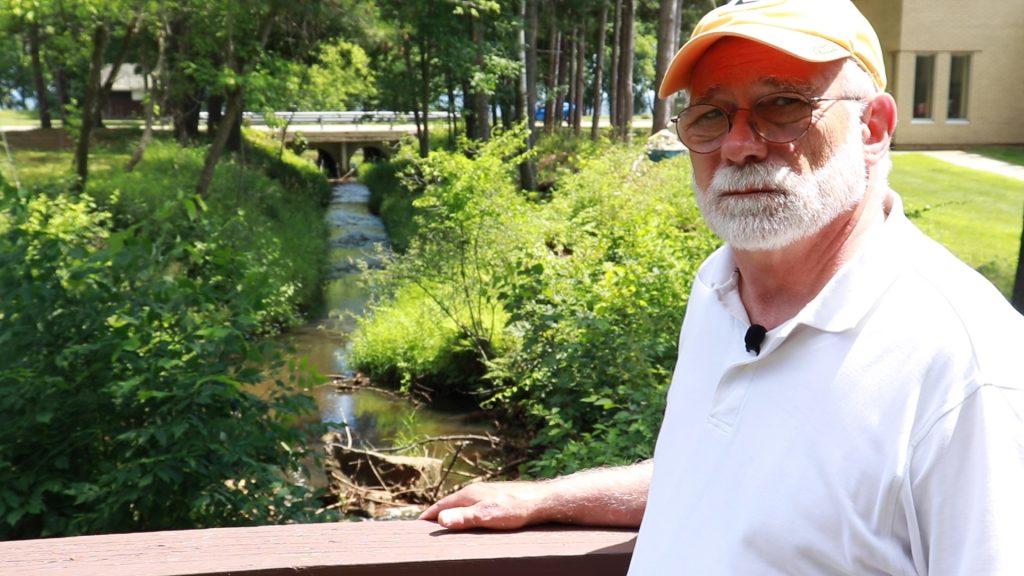

Soon after the news of the PFAS contamination became public, a group of citizens led by former Marinette mayor Doug Oitzinger banded together to demand transparency and accountability from Tyco and Johnson Controls.

Oitzinger and others want to know why Tyco chose not to tell neighbors about the threat of PFAS contamination in 2013, despite test results showing high concentrations of the chemicals in the soil and groundwater on its property.

“It’s a hazardous substance and they didn’t report it,” said Oitzinger. This is a crisis of contamination.”

The company says it chose not report the contamination because it believed the PFAS plume was contained to its property. Neighbors were not notified about the contamination threat until November of 2017, more than four years after the first test results.

“We have neighbors that have 600 parts per trillion in their drinking water,” said Ruth Kowalski. “And they let them drink it for four more years?”

“TIP OF THE ICEBERG”

But the problems with PFAS do not end there. According to DNR, much of the PFAS from Tyco’s fire training center also made its way to Marinette’s wastewater treatment plant through the city sewage system. The treated sludge from the plant—known as biosolids—was then used as fertilizer and spread on more than a hundred farm fields nearby. Experts fear some of the crops grown in those fields could contain PFAS.

“It’s scary. It’s like we’re at the tip of the iceberg here,” said John Kowalski.

Surface water contamination is also top of mind for many in Northeast Wisconsin. High levels of PFAS have been found in drainage ditches and streams that flow directly into Green Bay. In some cases, the tests showed PFAS levels well above 1,000 parts per trillion.

Oitzinger is concerned that surface water contamination could also lead to contamination of wildlife.

“We have deer that are probably consuming contaminated water,” he said. “We have ducks and geese, not to mention the fish out in the bay. So there are a whole lot of wildlife concerns about this contamination. It’s not only humans. It’s the environment and human health.”

The former mayor of Marinette is one of many calling on state legislators to act quickly by passing PFAS legislation. Oitzinger says it could be the difference in preventing future crises of contamination.

“We have PFAS problems all over this state, this just happens to be the worst one. And the one that will set the standard for how we’re going to treat every other PFAS problem.”